My thoughts on Kata and their importance…

In traditional martial arts, Kata are the techniques that

make up the core of study. Depending on whom

you ask, Kata can have different meanings and levels of importance. In more recent history, this has been a constant

source of controversy, with some dropping Kata entirely from their curriculum

and focusing, instead, on concepts, free exploration and adaptation.

In our Bujinkan organization, we have nine traditions, or

ryuha, each with their own structure of Kata.

There are Kihon (foundation) but then you get into levels of Kata, from

written Densho to oral Kuden. This is

how the arts have been preserved and passed on from generation to generation.

For myself, Kata have been like the perfect antagonist to a

fantasy novel. They are context-based,

coming from history and archeology at a time when people carried swords, wore

armor and even had basic firearms. In

the different histories of our ryuha, you have armored guys fighting aboard

ships, deploying guerilla warfare tactics, guarding dignitaries and their lords

from assassins, living in nature as warrior-monks, and so on. The histories are rich and culture and

legends, at a time in Japanese history when turbulent wars for power were

constant. Only when the wars ended,

Japan became unified and the overall need for martial arts changed, that you

began to have ritualized, codified and preserved traditions. Prior to that, martial arts were not

something publicly taught, there weren’t really any “dojos” and those who

taught were either privately training their students or taught

government/military forces in a more generalized and structured way.

Today, martial arts are not only a commercial industry, but also the needs and context today are not the same. But, the lessons learned from those Kata are still every bit applicable to learning. In my opinion, people miss the lessons those Kata taught. As the saying goes, they’ve missed the moon for the finger. They fail to understand that those who wrote down and shared Kata did so to convey certain lessons, lessons which we still need to learn if we are to truly learn the art we profess to study.

Today, martial arts are not only a commercial industry, but also the needs and context today are not the same. But, the lessons learned from those Kata are still every bit applicable to learning. In my opinion, people miss the lessons those Kata taught. As the saying goes, they’ve missed the moon for the finger. They fail to understand that those who wrote down and shared Kata did so to convey certain lessons, lessons which we still need to learn if we are to truly learn the art we profess to study.

If we take a Kata and first look at it in a narrow “Solution

A to Problem A”, then context matters and we’ll be trapped into finding no relevancy

to modern danger or situations. I mean,

really, are we likely to be attacked by a sword wielding Samurai looking to

take our head back as a trophy? Maybe a

terrorist or crazy madman might come at us like that, but the likelihood is

really far off compared to, say, Feudal Period Japan. But, if we take a Kata and dig into the

details, of what makes it work and why, we begin to learn about anatomy,

physics, kinetics, balance, leverage, and many other wonderfully universal

lessons that can be directly applied to modern application.

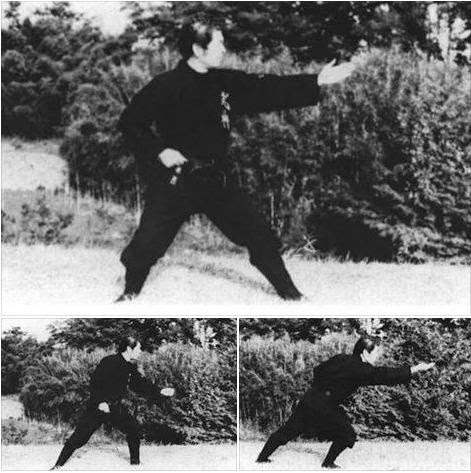

Let’s take a look at a basic Kata called Hicho no Kata, from

our Kihon Koshi Sanpo. Without “teaching”

this kata on a blog, let me at least share with you some key points that often are

missed. The starting Kamae (Posture) for

this Kata is called Hicho no Kamae. Your

lead foot is up on your rear calf and your lead knee points at your Uke, while

your hands are up to protect. The Uke

executes a strike to your gut and you do a downward, almost sweeping type of

"block" to receive it. This is called Gedan Uke

Negashi. From there, you do a front kick

to their midsection, at a target which is at a specific point at their stomach. This target is called Suigetsu.

Now, this raises several problems for the student. First, nobody is going to face off with an attacker while standing with one foot propped up, unless maybe you are the Karate Kid. Second, to kick that part of the attacker requires you to be almost perpendicular to the attacker’s torso. If they strike you with the standard Tsuki (thrusting with the body narrow, like a fencing thrust), the torso points out the side, making that target almost unreachable.

Now, this raises several problems for the student. First, nobody is going to face off with an attacker while standing with one foot propped up, unless maybe you are the Karate Kid. Second, to kick that part of the attacker requires you to be almost perpendicular to the attacker’s torso. If they strike you with the standard Tsuki (thrusting with the body narrow, like a fencing thrust), the torso points out the side, making that target almost unreachable.

To “fix” these two issues, a student will rationalize

themselves into changing the base form.

They will start in Ichimonji no Kamae, with both feet on the ground,

step out to the inside and raise the front foot as the opponent strikes. They change THEIR position. To them, this “fixes” the seemingly

vulnerable part about standing on one leg while being attacked and the part

about being able to reach the Suigetsu target.

Or they may even just forgo the Suigetsu and just kick wherever they can

reach.

So, what is learned from this Kata?

The way I was taught placed absolute importance on two

things:

1. Being able to maintain balance and structure while sweeping low to redirect the attack. You can’t move position, so you have to rely on the Uke Negashi to do the work. This involves dropping low on the base leg and catching the timing of when to push the attack out so that it misses you. This is VERY difficult and uncomfortable!

2. The importance of doing #1 correctly so that you move the Uke’s torso, twisting them on their axis, so that the front of their abdomen faces you for the kick to Suigetsu. This also means having to pull your kicking leg back into Hicho no Kamae, while maintaining balance and low Kamae. The final action in the Kata is to deliver an Ura Shuto to Uko, which is under the ear at the base of the skull. This requires going back to Hicho no Kamae after the kick to allow the Uke to “fall” into position for the Shuto. This is also VERY difficult and uncomfortable!

If you train this Kata in the manner I described, think of

the benefits you get to your body, your structure, balance, power generation

and delivery. You also learn to control

the Uke to create the openings, while developing precision in hitting specific

Kyusho (weak areas of the body).

No, it’s not a real fight.

It’s not meant to be. It’s a

learning tool. But, from the lessons in

there, you can apply them to a fight.

You learn how to receive an attack in a manner that takes power away and

breaks the structure of your attacker.

You learn how to attack specific targets as they appear. You develop strong, reliable and consistent

power, flexibility, control and balance in your lower body and core (a “must”

for Japanese budo arts).

How applicable are all those lessons to modern fighting

situations?

This is just one example, but you can begin to understand

the point. Kata are vessels containing

many lessons. Some are obvious, some not

so obvious. Others are so deep that,

even after almost three decades of training, I’m still discovering them (or

having a teacher reveal them to me).

Some people may ask when is a Kata no longer important or

when does it run out of lessons. My

opinion is that the only way that happens is when the student’s mind closes

itself off from them. Kata don’t need to

be changed. They don’t need to be

adapted. They need to be explored with

an open mind and curious attitude. The

lessons learned can be experimented with, isolated and developed on their own,

mixed in with various techniques and situations, and so on. But, they need to be discovered and learned

first and you can only do that when you dig deeply into the Kata that contains

them.

Just my thoughts.