I had some interesting discussions last week with someone I highly respect who is the head of an old Japanese martial art. We talked about how so many martial arts students simply lack passion and commitment in their training, how they just aren't excited (or at least expressing excitement) and when opportunities come to get around some of the top people in martial arts, their interest level is almost utterly non-existent. It is sad to see, as each year we lose some of the most notable and amazing figures from the martial arts world - and every year it seems less and less of these greats are there to take their place. He felt the same way I did, that each generation is weaker when it comes to producing martial arts masters on the same level or greater than previous masters.

In essence, the arts are dying.

Last week, I also had a great conversation with someone who is one of my highest ranking students. But, he is also a black belt in Aikido. He mentioned how their classes are so small, there are nights he texts his training buddy to see if he is going. He also said that the head instructor of this school also has stopped training with his teachers. He simply lost his passion as a student and just goes through the motions of presenting the art as he understands it.

Our conversation paralleled the exact conversation I had previously with the other gentleman - the arts are dying.

Why is this?

We deduced that our current society is so dependent on technology, instant results, and this notion that everybody is a winner. There is little or no struggle to get what you want when you can simply point and click. Video games have replaced sports. My own son no longer wants to play in sports, because his online gaming community is where all his friends are at anyway. Even in schools, failure rates are skyrocketing as a broken education system continues to lower the bar on what is expected to pass, because too many failures means the teachers and schools lose money and are blamed for "not providing quality education". So, society learns that failure is always somebody else's fault and holding someone to a high standard is somehow a negative.

In martial arts, we also see this trend. There are "fast track" promotions. You can buy a black belt program that guarantees receiving a black belt in a given amount of time or classes (instead of actually earning it, no matter how long it takes). There are so many marketing gimmicks designed to sell snake oil to generations of people willing to pay for convenience and instant gratification. One of the main reasons is simply commercial, or profit making, but also because schools who don't will not attract as many students and if they can't pay their bills, then the school closes.

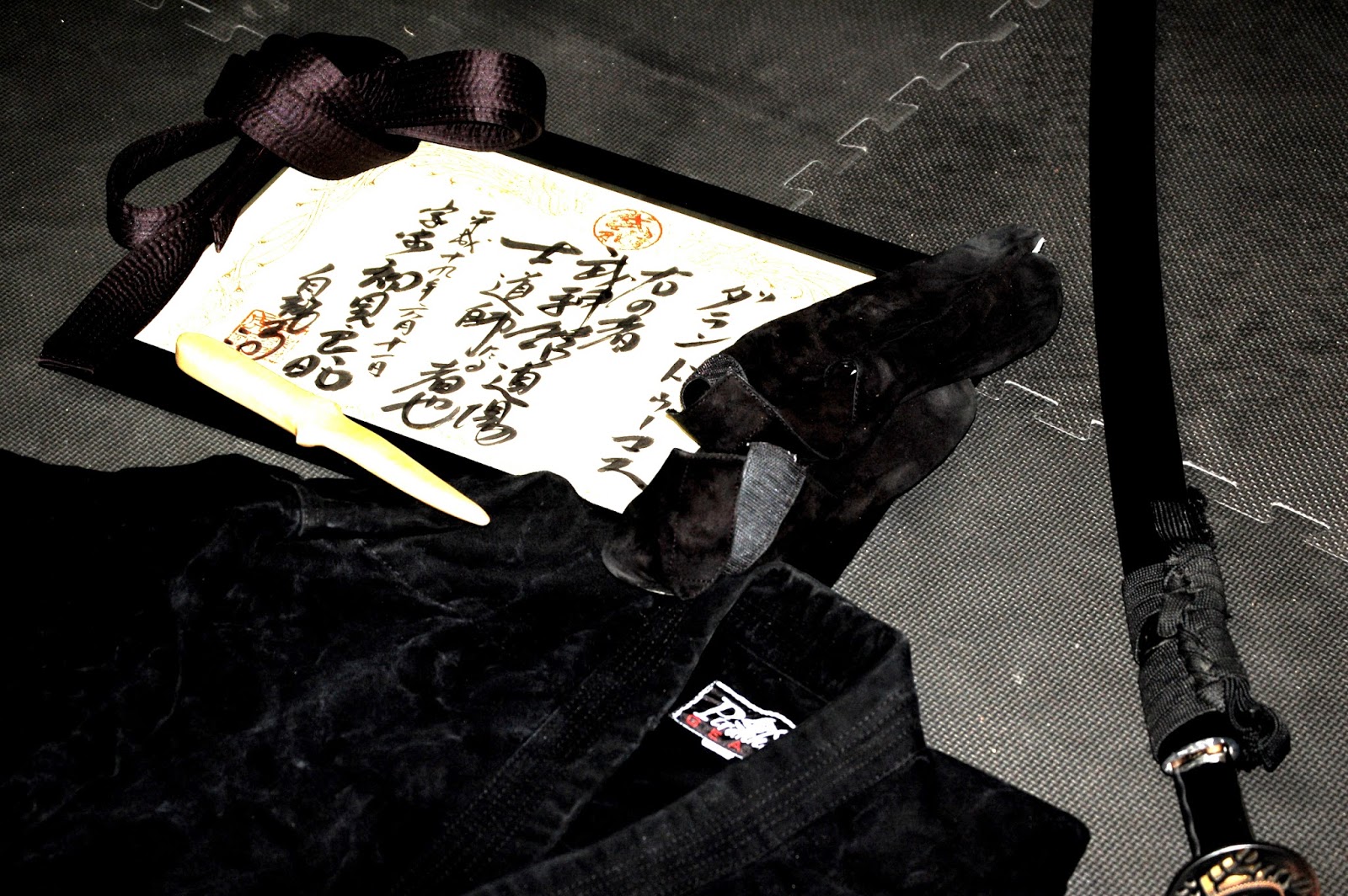

This leads me to my point and something brought up during these discussions. Gone are the days where prospective students had to prove themselves acceptable as students. Gone are the days when a student would practice the most simple thing, like a punch or a cut with a sword, over and over for hours. Gone are the days when a student would toughen their body through repetitions of striking a hardened surface to condition the hands, fingers, elbows, knees and such. Gone are the days when a student would travel hours just to learn a single lesson from their teacher and focus on just that until their teacher feels they are ready for another. Gone are the days when promoting in a school meant years of commitment, hard training and sacrifice. Gone are the days when the teaching of an old system was just as much a pursuit of history, archeology, language and culture, as it was training the body.

Gone are the days when a student's belt actually went from white to black from all the grime, sweat, blood and dirt gained from enough training.

And, gone are the days when students had passion so strong they would take advantage of every opportunity to train, instead of only when convenience and interest allow for it.

If I opened a school, new people came to sign up, and for the first week all I had them do was practice a low, extended punch over and over until their legs gave out, would they come back? What if I didn't use mats, just hardwood flooring, and had them practice rolls and break falls repetitively for the entire first week. Would they come back?

What if I told them they wouldn't reach their first belt rank unless they not only know a list of techniques, but also maintain regular attendance, show consistency in the quality of their training and follow up their class training with drills to practice at home? Would they do it? Would they do it beyond their first rank?

After several months of training went by, what if I held a ranking exam and some students didn't pass. Would the bitterness of failure discourage them from continuing, or would it inspire them to push harder for excellence?

A friend of mine in Japan mentioned to me how the younger generations of Japanese are losing interest in the old martial arts. They are more interested in sports. It's no different here. Many of the traditional martial arts classes in Japan are usually populated by more non-Japanese than Japanese. With the popularity of sport martial arts like MMA, young men and women are flocking to gyms instead of dojos. They have coaches instead of sensei. They want the excitement that comes from competitive sports - and there are entire industries built around it which are more and more common and available.

Hatsumi Soke wrote about how budo (and martial arts) are about humanity. This is because martial arts were started by humans interacting with each other in conflict. Back then, conflict was real, brutal and often deadly. Today, with the exception of violent assaults that happen from time to time, what society views as conflict is a Monkey Dance - a chest puffing slugfest by two drunk guys (or more). They also see sports like MMA on the same level as violence. Yet, they are not - at least from where the traditional martial arts came from. As a result, those old arts lose context and, thus, people lose a reason to actually learn it. They'd rather learn MMA, ground fighting systems, Combatives and any number of other modern methods. They don't care about history, culture and masters.

Thus, the arts are dying.

What people often fail to understand is quite simply this: The struggles that it took for a student to just be accepted as a student, the struggles it took for that student to progress and the struggles it took for that student to succeed, all forged a person into mastery of not just the art, but of himself. The quality of the spirit was revealed in what it took to just be a student and, those who eventually mastered the art, were amazing individuals who inspired the next generation and taught through their life examples. When you think about the old masters, they seemed larger than life! Although they were known for their art, what they had to share wasn't about any particular technique - it was their spirit, their intensity towards life and the wisdom that was gained from their pursuit of mastery. The kind of person that reached that level truly was a master, not by what they said, but by what they did. They walked the walk, not just talked the talk. They didn't have to prove themselves. You just knew it.

The arts were alive because the masters and their students were alive through those arts. The life force of the arts were the collective life force of all the masters and students in them. What about today? Are the old arts living vibrantly and powerfully, or are they getting weaker and weaker. Even if there are many students in the dojo, do you feel the collective life force is still weaker than it should be? Who bears responsibility for it? You? The teacher?

The arts are dying. That is a sad fact. But, they are only dying because people are letting them. Yet, the answer lies in the individual, as it only takes one individual to breathe life back into an art. So, are you that individual? Or, is your art dying within you, too.

Saturday, September 19, 2015

Thursday, April 9, 2015

Peeling the Onion - Thoughts on Forms

In the

Bujinkan, there are many very confusing things which are taught and spread

throughout. One of these things pertains

to the Kata, or Form/Technique, and its importance in training. We are taught to learn the form, break the

form, and finally transcend the form.

This is known as the Shu-Ha-Ri model, which is about as old as martial

arts. But, when you start digging into

the applications and interpretations of this in our regular martial arts

training, you find there really are many different, even conflicting, ideas and

applications of this.

Over the

decades I have been training, I have found myself being led in various

directions regarding the importance of “by the book” forms and techniques. I have trained with teachers who are purist,

sticking exactly to how things were originally written, and those who have

almost virtually discarded the original forms and practice methods they believe

are transcending the original design.

Most of the Bujinkan, I believe, is a mix of these two ideologies. For a very long time I had bounced around

somewhere in the middle, too, often leading to contradictory conclusions and

even leading my own students down this rabbit hole.

I will try

to give an example of this:

Student is

taught Technique A. Against his opponent’s

punch, he learns how to move out of the way, how to align his body correctly

and put up his arms to provide protection.

Then, he strikes the opponent’s arm with his arm and steps forward with

an open hand strike to the side of the opponent’s neck. He practices this over and over again until he

is able to do this off memory and less and less correction. He is learning about the importance of structure, balance and movement.

Next, he

learns that moving off at the right angle and right distance protects him from

a fast second punch, so he drills this until it becomes precise every

time. He learns that his upward block

hits the opponent’s arm at just the right angle and timing to cause their body

to turn. He practices this over and over

again until he gets that result every time. He begins to learn about anatomy and auto-response mechanisms, or how to create change and opportunity (cause and effect), as well as using the timing of reaction as cover for the next movement.

He realizes

that if he does this block just right, the side of the opponent’s neck is more

open and he steps forward and strikes it with greater accuracy at the right

point on the neck to cause the opponent to stumble back. Again, he learns more about anatomy, structure, balance, creating opportunity and controlling the opponent.

After many,

many successfully performed versions of this, he begins to realize he is moving

at the right angle, the right distance, hits the opponent’s arm correctly,

causes the right reaction and strikes the neck at just the right point, every

time with less and less variance. Now he is learning to embody the efficiency of the elements of the form into natural motion.

When the

teacher sees the student is ready, he teaches him that with more flow and

timing, instead of striking the opponent’s arm, he can draw out the arm and, in

so doing, cause the opponent’s body to turn in time with the strike, opening up

the vital point on the neck for the student to step forward and strike. Instead of separate actions of block and

step/strike, this begins to move as one motion.

This is practices over and over until it is done with precision in

timing, movement and targeting.

Once the

teacher sees the student has this down adequately, he encourages the student to

consider other options instead of striking the neck. Maybe he steps in and throws. Maybe he steps in and strikes other vital

targets. Maybe he steps in and steals a

weapon off the opponent. Maybe he doesn’t

step in and launches a kick instead.

And, since

we are a weapons based art, the student also sees the connection to doing the

same technique with a sword, long staff, short stick, knife, rope and

everything else.

Seeing this

progression, it becomes crystal clear that the student will never truly learn

how to perform the more advanced versions, never really “see” the next levels,

without focusing on the very basic mechanics and drill them over and over

again, without change or variance, until they become locked in enough that the

teacher feels the student is ready. That

is what I have come to understand as a true way to learn martial arts. Anything outside of that is so dangerous,

because it sets up false confidence with weak skill sets. Under pressure, they will break down and

fail.

I know this

might be controversial and I probably will take some heat from my opinions on

this, but I have arrived at this through my own trials, errors and

discoveries. I have also been around

long enough to see the results of how different people train and teach. But, I’m also a realist and know that even in

my own current thinking, training and teaching, I am forever still just a Work

In Progress.

Tuesday, March 10, 2015

Mad Libs Budo

Ever play that word game called Mad Libs, where you’re given

a short story and scattered throughout are blanks for you to fill in? You pick a noun, verb, adverb, adjective,

etc, and when it’s finished, you’re left with a funny story. Here’s an example:

“Charlie was a (noun) who loved to eat (noun). He particularly enjoyed the (color)

ones. One day, Charlie was (verb) and

some friends came by to visit. He

offered them a (noun), but didn’t have enough.

But, one of the friends brought a (noun) and they all had a great time

(verb). After they were finished, they

all decided to (verb). Charlie

accidentally (verb) really (adverb). He

was so (emotion) over it.”

If you fill in the parenthesis with the requested kind of

word (noun, verb, etc), then read it back, you will have a story that might be

a bit crazy, maybe funny, or even one that just makes sense. But, hand it to someone else, and you

generally will get a completely different story.

I use this analogy to describe what learning budo is

like. In the beginning, we have a blank

page. We receive words to start building

the story, but there are blanks. It is

human nature to want to fill in the blanks in a way that makes sense of what we’re

learning. However, as you can see, what

we choose to fill in those blanks can lead to very different outcomes,

sometimes silly and nonsensical, but sometimes quite logical – although still

different from the actual story.

To take up the path of a budo deshi (budo student) is to

seek to fill in the blanks, not with our own imagination, but with those things

which were originally there. We are

trying to uncover the story, not create our own. Although, it is easy for us to do and we’re

actually hardwired to do it, even on very subtle levels. We hate incompleteness. We hate to not have the whole story. So, we find ourselves thinking ahead, making

assumptions, relying on our own logic and reasoning, instead of patiently

working towards filling in the blanks with what is supposed to be there.

So, what is the danger of using one’s own logic and

understanding to come to completely rational conclusions, to fill in the blanks,

and arrive at a story that makes sense?

Because it’s not about just making sense out of

something. It’s about learning what we’re

supposed to learn, when we’re supposed to learn it. In a training context, we aren’t training to

beat up our Uke (partner or receiver of the technique). It’s not even about the “win”. It’s about unlocking the lessons, sharpening

the skills, of those pieces within the kata /waza or form. Everything is a gateway to something

else. Everything has layers to uncover

that lead to new layers. But, when we’re

too busy making our own story, we are off on our own path instead of the path

that opens the gateways and reveals the next layer in our understanding. We are not following in the footsteps of the

masters who have walked the very same path before us. In so doing, we evolve along our own,

uncharted lines.

In many things, exploring uncharted paths, taking risks and getting outside the box is a good thing. But, you have to consider the purpose of budo – it is about war and survival. The stakes are high, higher than anything else in life. If you were a soldier in Feudal Japan, your life expectancy on the battlefield was high. So, anytime you could learn from someone who had a technique that proved itself in battle, you would learn it as completely and accurately as you could. You would practice it over and over, exactly as you were taught, until it became a part of you. Then, when you were deployed into battle, you were ready to use it and hopefully it would give you a percentage chance of living another day. You wouldn’t risk your success on your own imagination, or someone who hasn’t proven their technique in battle. The risk would be far too high.

When I was in the Army, I got to know a new 2nd Lieutenant. We called them “Butter Bars” for the single,

rectangular brass bar they wore for their rank.

He told me that the single most important lesson he was told came from

his CO (Commanding Officer). The first

day he arrived, the CO called him in and gave him an introduction. Of all the things said, what stuck the most

was when the CO looked him in the eye and told him, “If you want to get crap

done right, if you want to go into war and come back in one piece, find the NCO

with the most hash marks on his sleeve, buy him a drink and listen to what he

says.”

The reason this was such important advice simply had to do with experience. The NCO already had completed one or more enlistment terms. He may have already done one or more tours in a combat zone. He probably had enough medals to fill up a trunk. Even though the 2nd Lieutenant out ranked him, even though the NCO had to salute and follow the orders of even the newest Butter Bar, the NCO had the knowledge, experience and training that was proven to work. So, it would benefit the new Lieutenant to follow closely his advice and direction.

The best officers listen to and take the advice of their NCO’s. They may out rank, they may give direction on

the larger purpose or outcome, but the actual nuts and bolts of how things work

the best, the method to make things happen, all falls to the experience,

training and knowledge of the NCO’s.

Is there any difference between that and martial arts which have survived through all the wars in Japanese Feudal history? How many martial artists act more like the bright eyed, young Lieutenant just out of college and try to dictate what they think would work in actual war, instead of relying on the wisdom of those who have actually survived it?

We do not have the benefit of spending time with those

Japanese warriors who lived and fought during the Warring Periods. But, what we do have are the densho, the

words and drawings which have been codified into scrolls. More importantly, we have the kuden, or

verbal teachings, that have been passed from person to person throughout the

generations. The wisdom is still there,

if we can let go of our own ego enough to listen. When we do that, we uncover the secrets, the

nuggets of learning, and are able to cross the gateways to deeper understanding

of the art we claim to be students of.

If we’re off on our own imagination, filling in the blanks

ourselves and creating our own stories, we fail to connect to that foundation

that existed long before we took our first breath. We fail to connect to those who have more

hash marks on their sleeves than we probably ever will.

And, as a result, when life and death matter, we may be

following our created path right into our own death.

My advice, from an old, crusty budo deshi who has learned from more mistakes than I care to remember? Be a humble student, not your own expert, and stay on the path already forged. You'll uncover a richness of the budo arts that you would never find on your own.

Monday, February 9, 2015

So, you want to be a black belt, huh?

So you want

to be a black belt?

There are

many things about martial arts which are silly, confusing and even misleading. We may think we know what we’re talking

about, but to a layman it must sound like gibberish. However, if we really stop to listen to

ourselves, to really think about what’s commonly said or written, we may find

that we really don’t understand. Our

Soke is a master at this, where we read or hear something and think we

understand – only to gain a totally different interpretation and understanding

later on.

One big

stigma that falls into this is the subject of belt ranks. It seems that, particularly in the Bujinkan

organization I belong to, there are so many mixed messages regarding the

importance of rank. You’ll hear people

say rank doesn’t matter. You’ll hear

people say rank is a personal thing between teacher and student. You’ll also hear people talk about the

yearning to be a black belt. That latter

part is what I want to write about here.

What does it

mean when someone says they want to BE a black belt, anyway? Are they really saying they want to be a

strip of black cloth that’s tied around the waist of someone? I doubt it, although nothing surprises me.

I believe

most people have some sense of what kind of person is a black belt wearer. For a new person, that usually means some

kind of measurable skill level beyond just a basic grasp of techniques. Some may even think it denotes a kind of

mastership. But, if we consider this

from different perspectives, we begin to see that a black belt really isn’t a

very concrete thing.

In a

curriculum based school, a black belt is an achievement based upon learning and

adequately performing the material required for the black belt. It’s a narrowly defined purpose and

result. Other schools may be more

holistic, focusing on gaining some level of understanding of principles, demonstrated

in a broader range of physical expressions.

Some may go so far as to not have any requirements, basing ranking

purely on the subject opinion of the teacher or recommendations from a

panel. In our Bujinkan organization, we

have all the above, making the image of a Bujinkan black belt something that

isn’t so clearly defined.

When a new

student expresses a desire to “be a black belt”, I feel some questions need to

be asked. What do they think being a

black belt means? Why is that so

important to them?

If one

wanted to EARN a black belt, then they are saying a very specific thing. But, to BE a black belt is relating more to

an ambiguous quality they wish to embody in themselves, an archetype of what

they believe a black belt student should be, which could encapsulate a wide

variety of images. To BE a black belt is

to conform themselves to their own fantasy image or expectation. To EARN a black belt means they conform to

what the school or teacher demands in order to receive a black belt. Although a student may often pursue both

aspects while achieving the goal of obtaining a black belt, the difference is

important.

In my

opinion, a student receiving a black belt needs to be satisfied with both BEING

and EARNING the belt. Anybody can put on

a black belt, but in so doing fraudulently, they are not BEING a black belt and

they certainly haven’t EARNED it. But,

one can earn a black belt and fail at being one. Many work hard to earn their black belt, but

because they have made the mistake of placing too much importance on receiving

the belt and not being the kind of person who has one, they end up stopping

there and never progressing. Some even

experience depression and frustration, due in large part to the black belt not

meeting their self-created expectations of what it is.

What, then,

does it really mean to BE a black belt?

That means not only earning it, but maintaining the same passion, drive,

focus and hard work it took to get there.

This is what takes you into the various grades of black belt. It takes being a diligent student in order to

EARN a black belt, but it also takes being a diligent student to BE a black

belt.

So, contrary

to the current popular opinions, rank does matter. But, it’s HOW it matters that the importance

is placed. Rank should be something

earned, but not as a one-time trophy or status or some kind of possession. It should be a measurement of your knowledge,

skill and experience. At the same time,

it should be something that fits what a person of that rank should be. Who sets that expectation? It is a combination of what you place on

yourself and the expectations of your teacher.

Earning

ranking isn’t something you do every few months or whenever testing is conducted,

like passing an exam for a class. You

are tested on it every day, every time you step onto the mat. You are challenged not only with learning the

skills it takes to reach that belt rank, but also in maintaining those

skills. From there, you have a platform

to build upon, to grow into the next higher rank. But, if you sit back on your ranking, putting

in just enough to maintain without continuing to refine, stop learning new

things and not growing in knowledge, skill and experience, you have failed at

being a student.

And being a

student is at the core of being a black belt.

Being a student is to have passion for learning, the commitment to train

honestly and with determination, and having the patience to keep going without

settling or letting the rank become a resting point.

The process

from white belt to black belt is deeply personal and contains many

challenges. It is the fire of challenge

and trials that creates growth. When a

new student begins, they will have an understanding of what earning and being a

black belt means. However, as they

progress, their own image of what it means to be a black belt will change. This is important, as it should serve to

guide them, like a beacon on a hill or an example to model themselves after. At the same time, they learn new skills and

build confidence when they see themselves executing them with greater

efficiency and ability. But, as they

progress, they discover there are always levels beyond what they thought they

knew and, in that, they begin to see that there is a balance between quantity

and quality. That hunger to evolve the

techniques they know, to reach those deeper levels, becomes weighted against

learning more and more techniques.

In those

pursuits, the meaning of ranking may change and carry less importance. For some, they are still clinging to ranking

over the substance of their training, showing it’s more important for them to

receive ranking than to grow as a student.

Instead of looking to sempai (seniors) and sensei (teachers) as examples

to try and emulate, they look to curriculum and textbooks for technical data in

order to do just what they need to earn the next ranking.

They are

chasing the belt instead of the art.

They may earn their black belts, but they will likely fall short of being

black belts.

So, you want

to be a black belt? Start by being a student

and never stop being that student. Understand

what it takes to earn a black belt from the teacher you choose to learn

from. Then, train as hard as you can and

let it come to you through your actions.

The day they put a black belt around your waist and give you your Shodan

menkyo (certificate), you’ll experience a new struggle. Everybody goes through it, some more than

others. You will have three things going

on at the same time, some stronger than others:

- You’ll wear your black belt as a symbol of your status, with an expectation that you are now proficient and an example for others. Instead of looking ahead to what’s next, you’ll want to show off what you have now.

- You’ll feel like you haven’t truly earned what you believe a black belt to represent. You’ll even feel somewhat embarrassed or ashamed to wear that black belt for the first time in class or have others refer to you as a black belt. You’ll train hard, trying to embody what you think you should be like in order to feel good about wearing that belt.

- You’ll just put it on and keep going, giving it little thought. You just see it as recognition from your teacher, nothing more, and you just keep showing up and training hard like you have all along.

The problem

with the first two is that they both place the belt rank in too high of

importance. Whereas, the first attitude

will eventually cause a student to fade away from training, the second could

lead to quitting out of frustration. It

could also lead to a serious lack of confidence, real confidence that one needs

to have to be a strong budoka. Humility

isn’t the opposite of confidence, so don’t confuse the two. The third one is the rarest, but likely more indicative

of what a successful, lifelong student embodies. However, few, if not most, never can really

have that as their main perspective.

We

all have a mix of the three. I can

attest to times when the first two were dominant. For me, often the higher rankings I’ve

received have left me feeling inadequate.

I felt I hadn’t quite earned it yet, so I would keep training. That’s a good outlook, but if I never felt

adequate for my rank, then I risk feeling like I’ve wasted my years of

training. At some point, I need to

accept the recognition from my teacher and keep training.

What I never

want to do is to settle or rest myself on my rank. Of all the three, that one is the most devastating

to a martial artist. Yet, we do have

moments where we enjoy our new rank, where the ego prods us to believe we are

better than a Kohai (junior student). It

happens to everybody, including me, and I have to just get with my Sempai and

Sensei to realize I have so much more to learn and grow that I can’t afford to

sit back and coast. In that regard, rank doesn't really matter, then, does it?

So, I just

accept what I am given and keep going, because I know that regardless how high of ranking I may receive, there will always be an endless path lying before me, drawing me deeper and deeper ahead in pursuit of knowledge, skills and experience. There is no belt, no rank, no certificate, which can replace the fire of that passion and the personal rewards of that endeavor. That's the secret to belt ranks and something that may be intellectually understood, but has to be experienced to be fully embodied in the heart.

Subscribe to:

Comments (Atom)